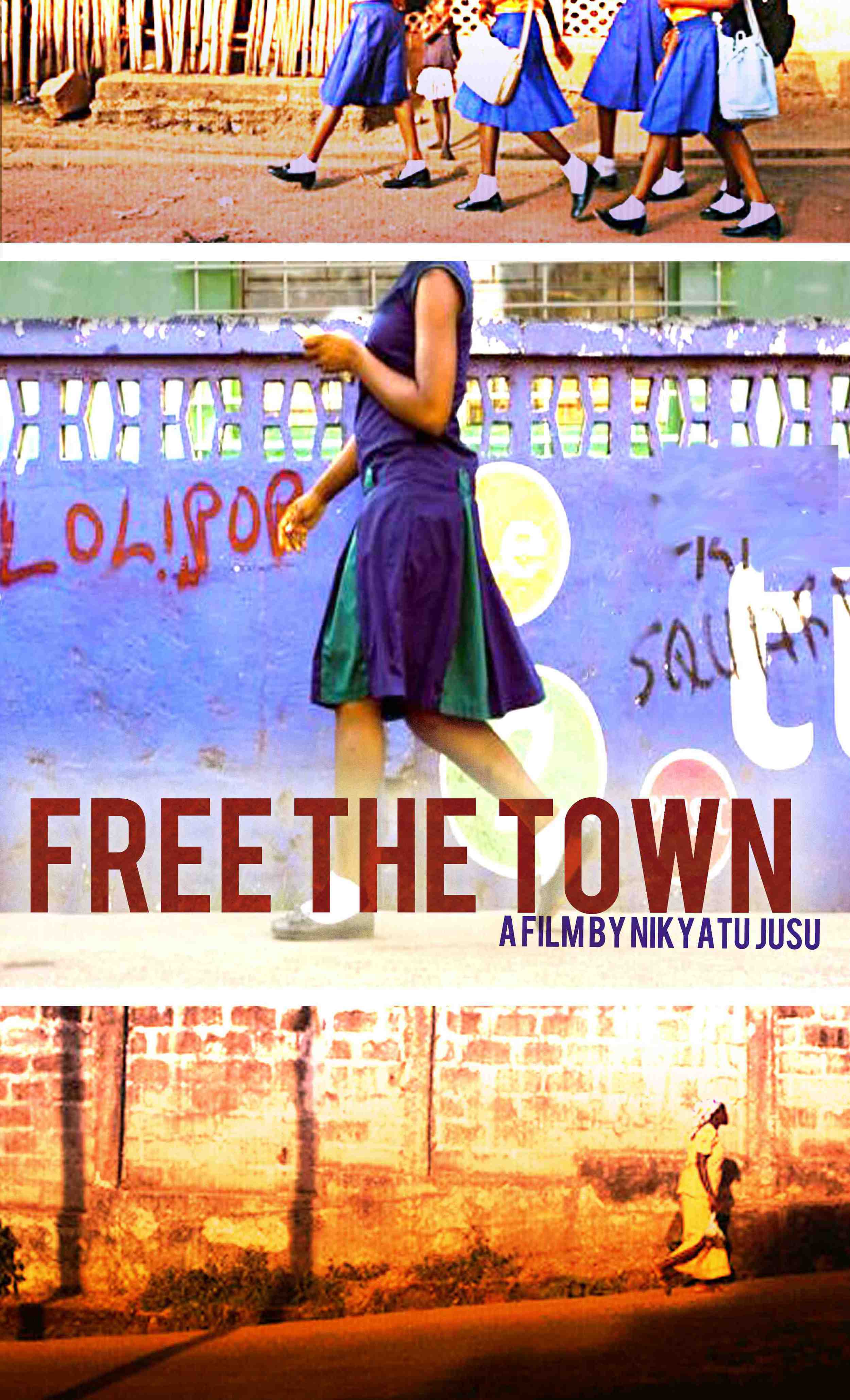

Durban FilmMart 4: FREE THE TOWN

Micah Schaffer

I recently attended the Durban FilmMart Co-Production market, which featured a diverse slate of documentary and narrative projects that are fostering collaboration between African countries and entities outside the continent. This is the fourth in a series of blogs about projects and issues related to co-productions in the South African industry.

NYU Graduate Film Alum Nikyatu Jusu participated in the Durban narrative feature market with her film Free the Town. Nikyatu went to Durban shortly after having attended Film Independent’s Fast Track program in Los Angeles.

I followed up with Nikyatu to see how things had developed since Durban, and what reflections she had about pitching her film to different industries around the world. (She and her producers have also been accepted to Independent Filmmaker Project’s Emerging Storytellers Forum, part of the IFP Film Week in September).

Nikyatu was born and raised in the U.S.; Her parents are from Sierra Leone. Free the Town is a coming-of-age drama that explores three interconnected stories about different strata of life in Sierra Leone. Free the Town has cross-cultural elements, including an African American character. The project’s local/global narrative blend -- which I find makes it unique and relevant -- presents certain financing challenges, which Nikyatu described to me.

According to Nikyatu, many of the production companies that she met with during FastTrack in Los Angeles had difficulty placing an independent African film like hers within their (mostly mainstream American) purview. Conversely, when meeting with European producers and grantmakers who had come to Durban to find African projects to finance, Nikyatu found that her background as a Sierra Leonian-American who grew up in the U.S. – and the African-American elements of her film – did not always fit easily into existing models of cultural and financial support for Africa filmmakers. Nikyatu’s short films have explored relationships between Africans and African-Americans, so there was some precedent – but still, she is pursuing subject matter that has not been extensively explored.

A primary goal of Global Film Connect is to find and track innovative partnerships (both creative and financial), so I was curious to hear about Nikyatu’s meetings with South African production companies. One prospect that was explored was to shoot Free the Town in South Africa, with locations there doubling as Freetown, the Leonian capital. Filming in South Africa would allow the film to take advantage of tax incentives there and would potentially qualify it for co-production status with other countries. (Blood Diamond was shot in South Africa and Mozambique, doubled for Sierra Leone).

Nikyatu’s preference is to shoot in Freetown itself – not only for the authenticity of the filmic experience, but to help engage and support the nascent local film industry. (Blood Diamond, by contrast, featured an American director, a Beninois star playing Sierra Leonean, and an American star playing an Afrikaner Rhodesian).

Free the Town aims to cast Sierra Leone in its vibrant present, a culture that is more rich and expansive than the stereotypes of its war-torn history. It will be interesting to see what kinds of international collaboration prove to be effective in getting this film made. This is a project worth keeping an eye on.