Crowdfunding - Patronage or Purchase?

Micah Schaffer

I recently attended two great Aspen Institute events that dealt with society’s investment in the arts.

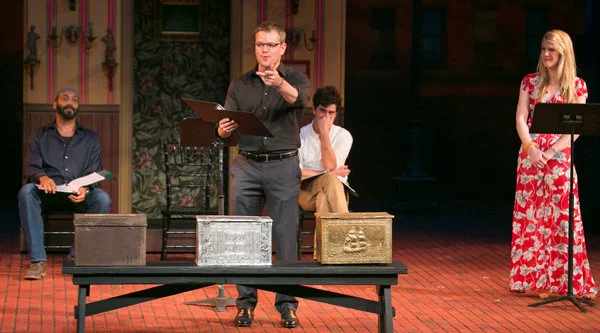

The first, entitled “What Are We Worth?: Shakespeare, Money, and Morals” combined Shakespearean monologues about money – performed by Matt Damon and Alan Alda, among others – with a town-hall style discussion led by Harvard professor and social philosopher Michael Sandel. The crux of Sandel’s argument is that while marketplaces are a necessary part of society, there are certain things that should be excluded from and protected from market forces. Up for debate was the question of whether arts should be among these. (A question that would, on average, be answered very differently in Paris than it would in Hollywood).

In thinking about the future of the Co-Production, I’m considering different types of film economies and their relationship to the global marketplace. One broad trend I anticipate is that there will be increasingly greater collaborations between private and public money the world over. Financing for the arts -- especially expensive arts like moviemaking -- will be subjected to the marketplace of audiences’ ideas and tastes. But films will also continue to be partially shielded from the marketplace by the patronage of those who are willing to pay for their existence without expecting financial gain in return.

So where does crowdfuding fit into all this?

Several CRI posts by the Grassroots Distribution team have dealt with the game-changing nature of crowdfunding – addressing the benefits of gift economies and the donor-versus-investor paradigm shift that many see occurring.

This brings me to the second Aspen Institute event, a discussion on “Democratizing the Arts” with Yancey Strickler of Kickstarter and Charles Best of DonorsChoose.org.

One of the things that struck me during this discussion was the blurring of lines between Non-Profit and For-Profit entities that has seemingly emerged with crowdfunding. DonorsChoose.org, a Non-Profit that channels funds to specific need requests posted by teachers, functions very much the same way as (the For-Profit company) Kickstarter.com. Both platforms facilitate the actualization of something that the audience/donor would like to see exist in the world.

Neither of these offer a financial return on investment for the donor, but they do both offer an assurance that by giving money, you are purchasing/funding the creation of a specific product or service. In the case of the now-ubiquitous rewards for Kickstarter Donors, you’re also likely pre-purchasing a DVD, digital download, or ticket to a screening of the film.

So is crowdfunding a movie patronage or purchase? It seems to be both. And it’s an important question because mounting a crowdfuding campaign and mobilizing an audience’s participation (financial or otherwise) is now a prime directive of many producers. For these projects, the relationship between the filmmaker and their audiences/customers/supporters is now exercised to a great degree in the fundraising stage.

Last year was the first in which money given to the arts through Kickstarter outpaced funding from the U.S. National Endowment for the Arts. It will be very interesting to see how the landscape has shifted by the time this benchmark is reached in a European country with a more collectivist, government funded film industry. But I’ve spoken recently with a number of European filmmakers working on first features who are foregoing the (stable and) traditional public funds of their home countries in favor of a more flexible crowdfunding base – which they believe allows for a quicker turnaround time and more artistic control.

Perhaps what is so promising about the future of filmmaking, and expensive artistic endeavors in general, is that the modern Medicis can be anywhere in the world. And an audience member of modest means can patronize your film and purchase it in advance – which in turn allows it to exist in the first place.

In the rosiest view of crowdfunding, it is indeed a new kind of marketplace – one in which return on investment means getting to see a film you wanted to be made.